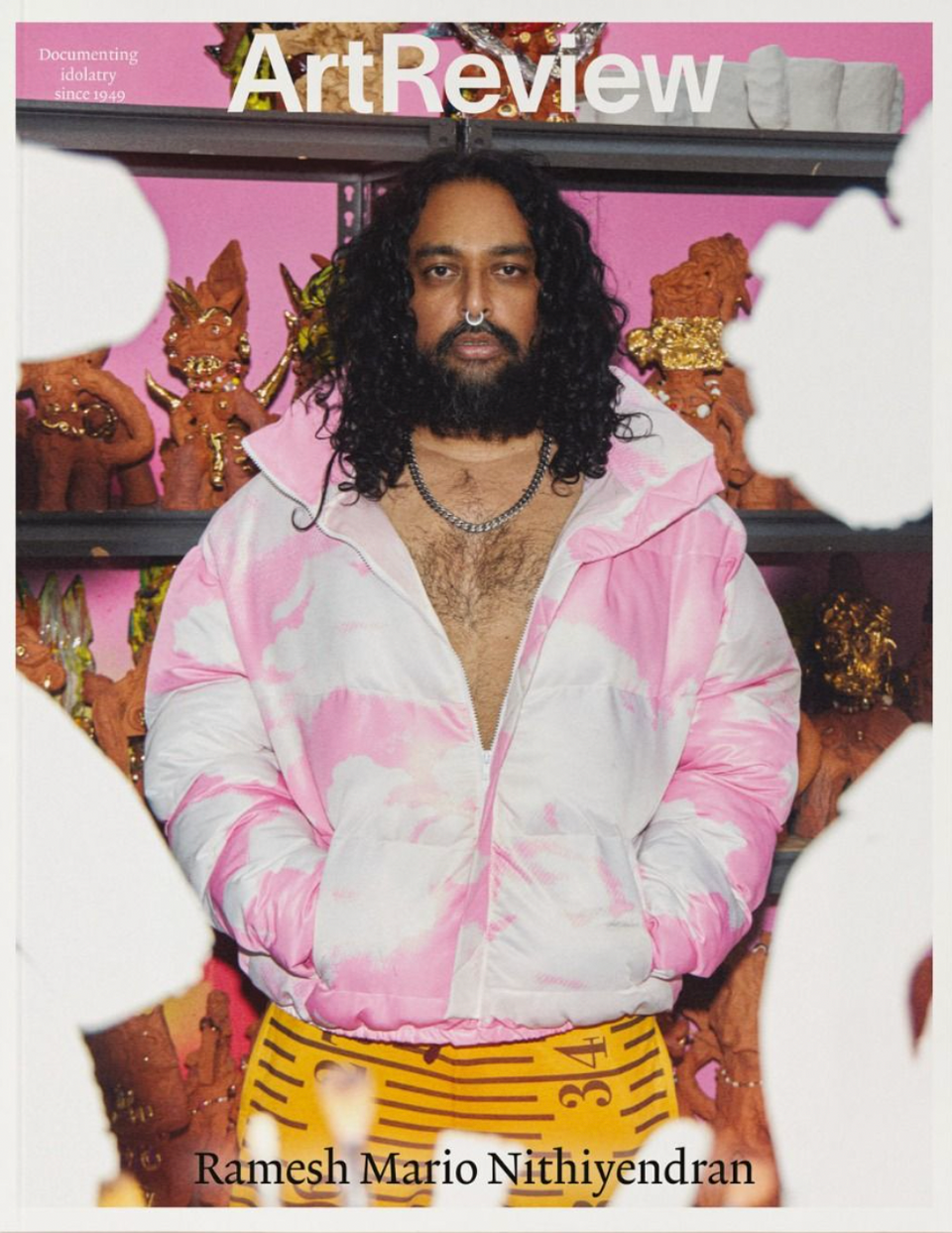

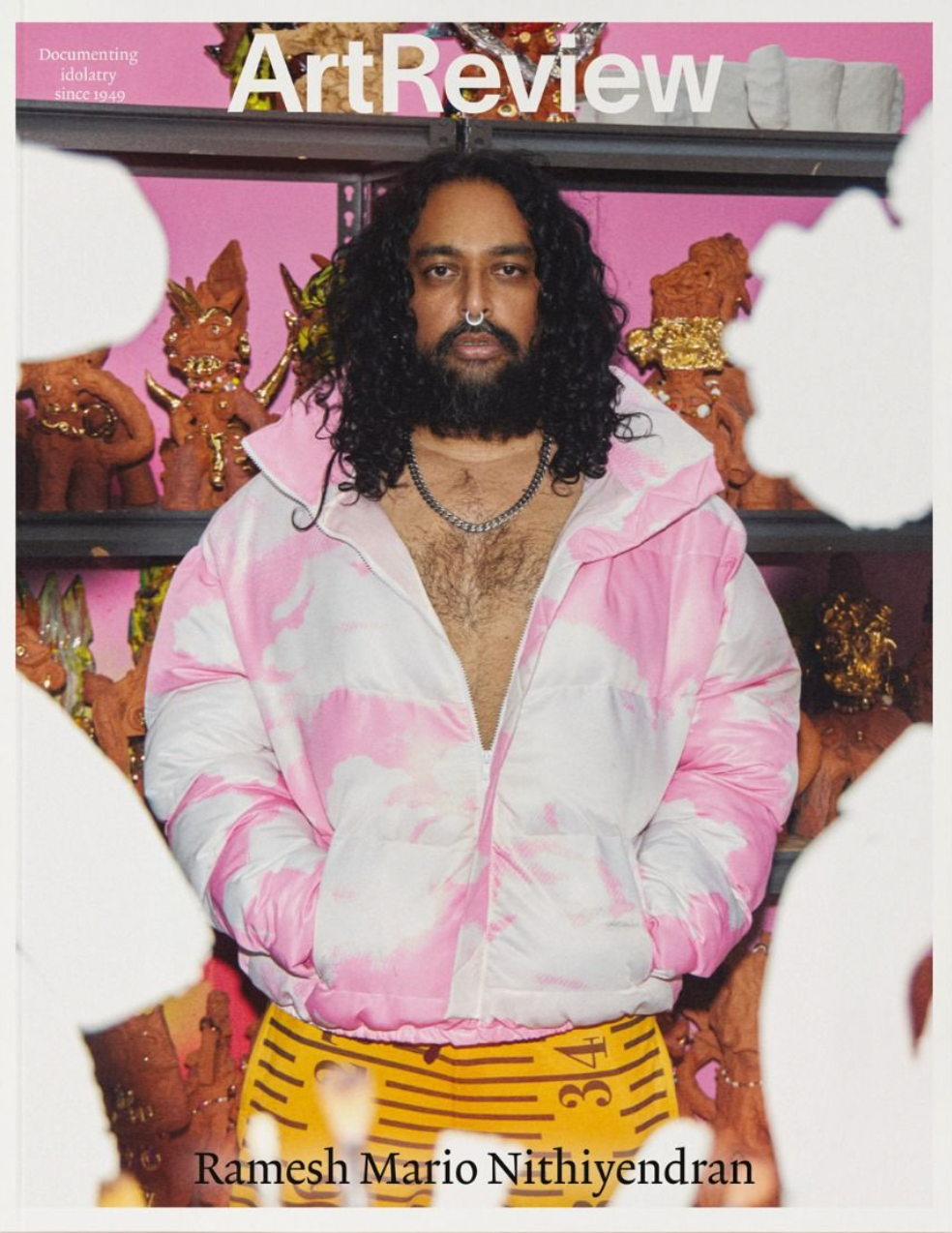

Art Review Vol. 25 No. 8

$12

Nathalie Olah and Mitch Speed consider the subject of ‘Art and Class’ in a two-essay focus on, respectively, how class and those in the position to arbitrate what exactly that means affects representation and means of production. ‘Cheap, fast consumerism is the only available source of joy to people robbed of time, freedom and choice,’ Olah writes, ‘and to have those objects of desire ridiculed and mocked in the space of the gallery, is too easy, too low: the pitiful and grotty demand for cheap goods as the symptom of a sick society in perpetual decline? It’s scornful.’ Olah points to the work of Finnish artist Pilvi Takala (whose performance art centres around state control, surveillance and social structures) and Germany-based artist Sung Tieu (whose multimedia work interrogates cultural class divides and the dehumanising web of state apparatus and bureaucracy), as examples of ways in which art can confront issues of class by revealing the conditions that lead to the creation of social divides. Meanwhile, Mitch Speed dissects the ways in which the artworld, and being an artist within that world, is increasingly limited to the purview of the already-wealthy, or those who have access to it – and their tastes and judgements of what makes ‘high’ art. As well as economic class divides, Speed points to discrimination based on race, ethnic background, sex, religion, worldview, disability, age and sexual identity as forms of ostracisation from an artworld that ‘has been so thoroughly annexed by the ruling class that we have lost the ability to imagine how it could meaningfully serve anyone else.’

Mariacarla Molé looks at the format of diary writing as a method for preserving events and moments in sitú. In 2009, art-historian Vittoria Martini was invited by Swiss artist Thomas Hirschhorn to attend his Bijlmer Spinoza-Festival project in Amsterdam, which took the form of a temporary monument and activated by lectures, workshops, published newspapers; she spent two months (the duration of the artwork) documenting and trying to give definition to a work that was configured as a festival but affirmed (by the artist) as a single sculpture. In light of Martini’s recently published book, Thomas Hirschhorn: The Bijlmer Spinoza-Festival, The Ambassador’s Diary (2023), Molè considers how the narration of an art event, experienced both collectively and individually, but written from the perspective of an art-historian, is expected yet fails to remain objective in light of Martini’s role as a resident ‘ambassador’. This experience led to a new methodology of art historical writing termed by Martini as ‘precarious art history’: Molè explains, ‘It’s a form of writing that renounces theory for experience, critical distance for the deeply involved; that imposes itself as action and reaction in a productive and tangible way, rather than as theoretical and invisible thinking.’ And one that reflects the temporary and precarious nature of Hirschhorn’s sculptural event spaces.

Details

- Format: Paperback

- Pages: 110

- Date: November 2023

Shipping

You have three shipping options at checkout:

- Best Way: Your order will ship within two business days via UPS or USPS priority or first class, depending on the size and weight of your package.

- 2-Day Express: Your order will ship the following business day via FedEx or UPS 2-Day Express.

- In-store Pickup: Add items to your cart and proceed to checkout – there, select Local Pickup in Shipping Options. Once your order is ready to be picked up, you will be notified by email.

Once all of your items are ready for pickup and you've received your Ready for Pickup notification (remember: don't come to the store unless you've received this).

To collect your in-store pickup order once you have received the "Ready for Pickup" notification, please come to the Shop (located in the main lobby off Vineland Place) during the Walker Art Center's open hours. We are currently unable to do curbside pickup.

Shipping rates depend on the selected shipping speed and weight/size of the items. Please allow several days for your order to be processed and shipped.

If you have any additional questions please contact shop@walkerart.org.